To look at a Persian carpet is to gaze into a world of artistic magnificence nurtured for more then 2,500 years. The Iranians were among the first carpet weaver of the ancient civilizations and, through centuries of creativity and ingenuity building upon the talents of the past, achieved a unique degree of excellence. The carpet is the finest and most exquisite form of expression and Iranian can find and the best specimens available today rank amongst the highest level of art ever attained by mankind. Even today, with Iranians increasingly being swallowed up in the whirlpool of a fast expanding industrial, urban society, the Persian association with the carpet is as strong as ever. An Iranian’s home is bare and soulless without it, a reflection on the deep rooted bond between the people and their national art.To Trace the history of the Persian carpet is to follow a path of cultural growth of one of the greatest civilizations the world has ever known. From being simply articles of need, as pure and simple floor entrance covering to protect the nomadic tribesmen from the cold and damp, the increasing beauty of the carpets found them new owners – kings and nobleman, those who looked for signs of wealth or adornment for fine buildings.

Many people in Iran have invested their whole wealth in Persian carpets – often referred to as an Iranian’s stocks and shares – and there are underground storage areas in Tehran’s bazaar that are full of fine specimens, kept as investments by shrewd businessmen. And for many centuries, of course, the Persian carpet has received international acknowledgment for its artistic splendor. In palaces, famous building, rich homes and museums throughout the world a Persian carpet is amongst the most treasured possessions. Thus, today Iran produces more carpets than all the other carpet making centers of the world put together.

“Sara-e Mozafari carpet bazaar, Tabriz”

The element of luxury with which the Persian carpet is associated today provides a marked contrast with its humble beginning among the nomadic tribes that at one time wandered the great expanse of Persia in search of their livelihood. Then it was an article of necessity to protect the tribes from the bitterly cold winters of the country. But out of necessity was born art. Through their bright colors and magical designs, the floor and entrance coverings that protected the tribesmen from the ravages of the weather also brought gay relief to their dour and hardy lives. In those early days the size of the carpet was often small, dependent upon the size of the tents of room in which the people lived.

Besides being an article of furniture, the carpet was also a form of writing for the illiterate tribesmen, setting down their fortunes and setbacks, their aspirations and joys. It also came to be used as a prayer mat by thousands of Muslim believers.

Thus began a process of people handing down their skills to their children, who built on those skills and in turn handed down the closely guarded family secrets to their offspring.

“Vakil Bazzar, Shiraz”

To make a carpet in those days required tremendous perseverance. Even when carpet making developed to the stage of workshops, with several employees working on the same carpet, it was a question of months and often years of painstaking work. The leader would dictate through a series of chants to the other workers the color of the individual strands of wool to be knotted. When the time came for the tribe to move on, the loom had to be dismantled and the unfinished carpet folded as best they could. The following season it had to be put again at some new oasis.

Although cotton came to be used for the warp and weft of the carpet, the herds of sheep that surrounded the tribes provided the basic material, wool. The cold mountain climate provided an added advantage in that the wool was finer and had longer fibers than wool from sheep in warmer climates.

“Wool and cotton are used in weaving the carpet”

A key feature in making the carpets was the bright colors used to form the instricate designs. The manufacture of dyes involved well kept secrets handed down through the generations. Insects, plants, roots, barks and other substances found outside the tents and in their wanderings were all used by the ingenious tribesmen.

Before the dyeing process could begin, the wool had to be washed and dried in the sun to bleach it. The clean wool as then spun by hand. Since the tribes were constantly on the move and had only small vessels in which to hold the dyes, the dyers were unable to achieve a uniformity in shades, with yarn displaying varying tones of the same color. The wool was loosely dipped into dyeing vats and left for a time that could be judged only by the expert craftsman. Then the wool was left to hang without being squeezed, which would have left an uneven coloring. Later the wool was dried in the sun.

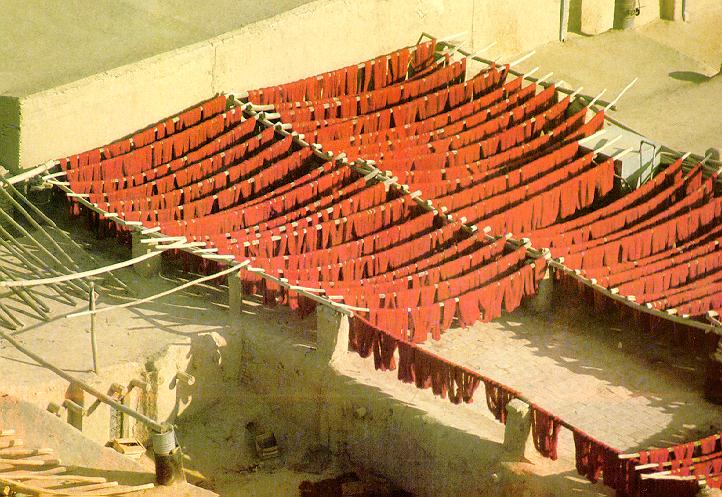

“Dyeing in Kashan”

Because the wool and cotton and silk used in marking the carpets are perishable, very few of the earliest carpet are now in existence. The earliest known Persian carpet was discovered by Russian Professor Rudenko in 1949 during excavations of burial mounds in the Altai Mountains in Siberia.

The Carpet had been preserved purely by chance/ Soon after it had been placed in the burial mound, grave robbers raided the mound. They ignored the carpet but, threw the opening they left, water poured into the mound and froze, thus protecting the carpet from decay. Called the Pazyryk rug, the carpet has a woolen pile knotted with Chiordes knot. It’s central field is a deep red color and it has two wide borders, one depicting deer and the other Persian horseman. .It dates from the fifth century B.C. and is now kept in the Hermitage Museum of Leningrad. Another rug found in the same area, this time with a Senneh knot, dates to the first century B.C.But, long before that historical records show that the court of Cyrus the Great, who founded the Persian monarchy over

2,500 years ago, was bedecked by magnificent carpets.

Classical tales recount how Alexander the Great found carpet of a very fine fabric in Cyrus tomb.

The next great period in the history of Persian carpets came during the sassanian dynasty, from the third to the seventh century A.D. By the 6th century Persian carpets had won international prestige and were being exported to distant lands.

And in this time was created one great carpet which was a spectacle of overwhelming splendor. The spring or winter carpet of Khosrow was made for the huge audience hall of the palace at Ctesiphon and depicted a formal garden. It held a political significance as an indication of the power and the resource of the king and its beauty signified the divine role of the king.

When the Arabs defeated the Persians and took Ctesiphon, they carried off the carpet as part of their fabulous booty and it was eventually cut up into small fragments and divided among the victorious soldiers.

Yet its magnificence lived on, inspiring subsequent history, poetry and art and helping to sustain Persian morale for centuries. It also provided a source of inspiration for subsequent carpets but, although many have tried, not even the most skilled have been able to equal its spellbinding design.

Certainly when the Mongols invaded the country in the 13th century they found many Persian homes and tents boasting local carpets. But for the next two centuries, the artistic life of the country, including carpet weaving, declined under the influence of the devastation wreaked by the Mongols. But, among his few graces, the conqueror Tamerlane spared artisans from his bloody havoc and had them sent to his palaces in Turkistan. Under his successor art began to flourish once more. His son Shah Rokh put a great emphasis on Persian carpets and outstanding specimens began to appear once more from court subsidized looms. The lavish royal support guaranteed the highest skills and the finest materials money could buy. Once more the art was for a great climax.

The climax came with the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century. When Shah Ismail occupied the throne in 1499 he began laying the foundation for what was to become a national industry that was the envy of surrounding countries.

The most famous of the kings of this era, Shah Abbas, more than any one transformed the industry, bringing it from the tents of the wandering nomads into the towns and cities. In Isfahan, which he made his capital, he established a royal carpet factory and hired artisans to prepare designs to be made by master craftsmen. He charged officers of the crown to ensure that the integrity of the industry was maintained and in his period the art of carpet weaving once again achieved monumental proportions. The best known carpets of the period, dated 1539, come from the mosque of Ardebil and, in the opinion many experts, represents the summit of achievements in carpet design. A complex star medallion dominates a rich system of stems and blossoms on a vivid indigo field. The larger of the two is now kept in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum while the other can be seen at the Los Angles County Museum. Excellent silk animal rugs were woven in Kashan while, to the north of Isfahan, weavers turned out the distinctive vase carpets. Rugs of great beauty were also woven in Kerman, Yazd, Fars, and Khuzestan. Shah Abbas also developed the use of gold and silver thread carpet, culminating in the great coronatio carpet now held in the Rosenburg Castle, Copenhagan, which has a perfect velvet-like pile and gleaming gold background.

“Carpet Weavers, Ghashghaie tribe, Fars Province”

These carpets, of course were made for the court and the great nobles, and were protected as well as any golden treasure. They had special custodians and, even when they were brought out for state and other special occasions, were usually covered with another light fabric to protect them from wear. Growing demand from the great royal courts of Europe for these gold and silver threaded carpets led to a great export industry. A large number went to Poland after King Sigmund specially send merchants to Persia to acquire them. King Louis XIV of France even sent his own craftsmen to Persia to learn the trade.

“Carpet Weavers, Ghashghaie tribe, Fars Province”

As the 17th century wore on there was an increasing demand for luxury and refinement. A set of silk carpets woven to surround the sacrophagus of Shah Abbas II achieved such a rare quality that many mistook them for velvet. But they were the last really high achievement in carpet making from that era in Persian history. Somehow, inspiration steadily began to slacken and, as the court became increasingly improvised, the quality of the craftsmanship began to fall away.

When Shah Abbas’ capital city of Isfahan was sacked in 1722 a magnificent period in the history not only of carpet weaving but of art itself came dramatically to an end. The great carpet weaving fell back into the hands of wanderings nomads who had maintained their centuries-old traditions and skills, apart from a few centers, principally Josheghan, Kerman, Mashad, and Azarbaijan. Even the low school rugs these centers produced were in danger of being ruined as an art by the growing demand from the West in the mid 19th century for quantity at the expense of quality. Cheap, dyes, low quality wool, chemical washing and even meaningless designs supplied by the European importers brought the industry almost to its kness. After sporadic and largely an successful efforts to stop the rot, the government took drastic action and confiscated the carpets in which cheap days and low quality wool had been used. The dye Masters soon came to their senses, with it began a new era of revival for the carpet crafts. The Iran Carpet Company and a school of design were established in Tehran to restore the integrity of Art and to study and build the great works of the 15th and 16th centuries.

“Washing Carpets at Cheshmeh-Ali near Tehran”